WASHINGTON — The Supreme Court docket has gotten a good quantity of reward for the best way it adjusted to the coronavirus pandemic: listening to a

WASHINGTON — The Supreme Court docket has gotten a good quantity of reward for the best way it adjusted to the coronavirus pandemic: listening to arguments by convention name, with the justices asking questions separately so as of seniority, and the general public allowed to hear in.

The 10 arguments the court docket heard over the previous two weeks have been orderly and dignified, and a few individuals thought the new format was a significant improvement over the unruly free-for-all that characterizes oral arguments within the courtroom. There have been few glitches, placing apart what actually gave the impression of a flushing toilet, and the questioning was characteristically sharp and delicate.

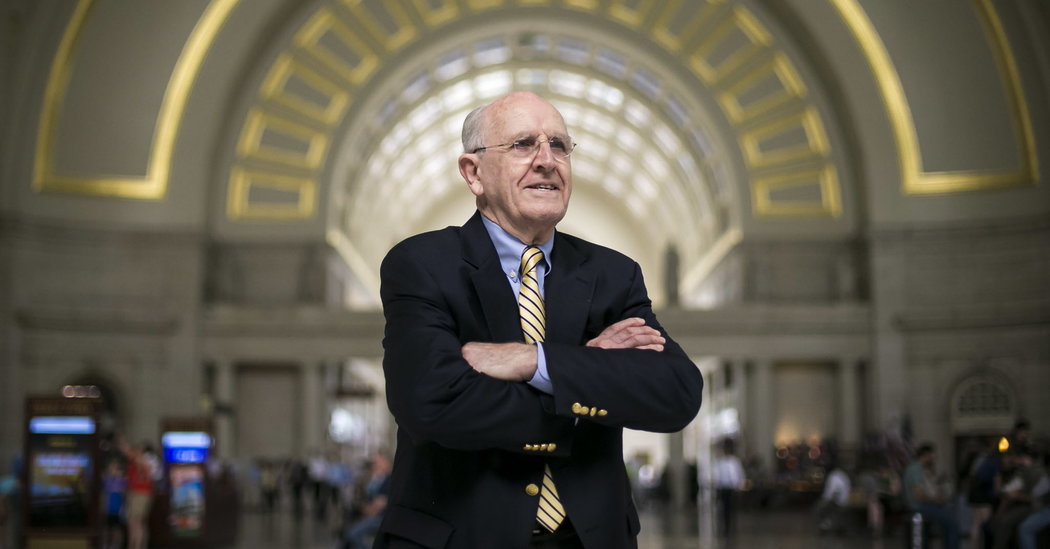

However there was a notable dissent, and it got here from an observer with distinctive {qualifications}. Lyle Denniston, who has attended extra Supreme Court docket arguments than every other journalist and fairly probably greater than anybody alive, issued a invoice of particulars objecting to the brand new format after the second conference-call argument.

He was significantly vital of the function Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. assumed, slicing off his colleagues’ questioning in an obvious effort to maintain the proceedings to the allotted hour. “This harms equal standing of every Justice,” Mr. Denniston wrote on Twitter, “offers the CJ arbitrary energy, diminishes cross-bench exchanges, promotes wool-gathering by attorneys, prizes order over depth, lets know-how triumph, appears amateurish.”

Mr. Denniston, 89, attended his first Supreme Court docket argument in 1958. Over the subsequent six a long time, he lined the court docket for The Wall Avenue Journal, The Boston Globe, The Baltimore Solar, Scotusblog and different information shops till he roughly retired in 2017. He’s now the dean emeritus of the Supreme Court docket press corps.

On the cellphone the opposite day, I requested Mr. Denniston whether or not there was something useful within the new means of conducting arguments.

“It’s very laborious for me to be charitable about it,” he stated, “as a result of I see so many flaws in it. The one advantage is that the court docket was publicly exhibited because it did its work. There’s a civic worth in that. However the course of when it comes to what we actually want the Supreme Court docket to do, which is to resolve these dreadfully essential constitutional and statutory and cultural questions, we simply can not have them doing it by a course of that’s so inherently flawed.”

The purpose of oral argument, he stated, is to permit the justices to speak with each other about how they see the case. The attorneys have their say of their briefs, he stated, and the arguments are the beginning of judicial deliberations.

“My premise has all the time been that argument is for the court docket and never for counsel,” he stated. “The justices use the arguments to attempt to affect one another or to attempt to gauge how one another is considering.”

Two points of the phone arguments, neither strictly crucial, annoyed that aim. One was having the justices converse in lock-step order. The opposite was making an attempt to restrict arguments to the same old hour, requiring the chief justice to chop off questioning.

“The chief’s function was a lot, a lot too heavy,” Mr. Denniston stated. “He was often making a subjective judgment about when counsel had stated sufficient or when a justice had requested sufficient. He was trapped within the mechanics of it. He was not solely slicing individuals off midsentence, he was slicing them off in the course of a thought.”

To make certain, permitting the justices to leap in each time the spirit moved them risked cacophony. However the time restrict may simply have been distributed with, and justices may have been allowed to ask all of the questions they wished to, one after the other.

Even with Chief Justice Roberts’s aggressive efforts, most of the arguments lasted 90 minutes or extra. Letting them run longer would have addressed not less than one among Mr. Denniston’s issues.

By historic and lots of worldwide requirements, an hour for an argument in an essential case will not be a lot time in any respect. When Brown v. Board of Training, the varsity desegregation case, was first argued in 1952, the court docket sat for greater than eight hours over three days.

“What’s the strongest argument you may make for limiting a profoundly essential inquiry to 60 minutes?” Mr. Denniston requested. “What’s the magic behind 60 minutes?”

He did see one shiny spot within the phone arguments: They allowed the general public to listen to insightful questions from Justice Clarence Thomas, who ordinarily doesn’t take part in arguments held within the courtroom.

“I’m one of many only a few, significantly within the media, who’ve lengthy been impressed with the depth, studying and originality, and the juridical high quality, of Clarence Thomas’s work,” Mr. Denniston stated. “And I’ve all the time thought that the general public notion of him was nearly to the purpose of tragic as a result of Clarence Thomas is a a lot, a lot better Supreme Court docket justice than his silence has invited individuals to conclude.”

I requested Mr. Denniston whether or not the court docket may retreat from permitting stay audio protection of its arguments as soon as issues returned to regular. Positive, he stated.

“There shall be no change in anyway,” he stated. “I totally count on that if the pandemic permits them to be on the bench in October, we received’t see one little bit of distinction.”