What you see is not always what you get. When a judge hands down a 16-year terrorism sentence it’s really eight years in custody with the rest on parole. The set-up is a bit of a swindle dating back to the 1960s, backed up by journalists who like a big number for the headline – myself included.

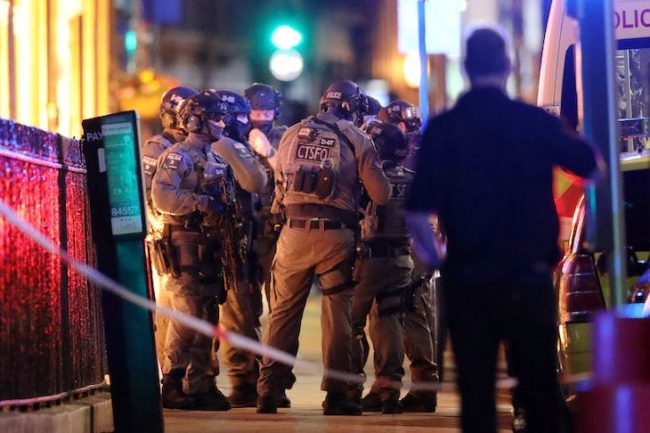

In the Queen’s Speech last month, the government promised to extend custodial sentences for terrorists as a reaction to the London Bridge attack on 29 November in which Usman Khan stabbed two criminologists to death just a year after he was released from a ’16-year’ terrorism sentence halfway through.

Boris Johnson and Priti Patel are still not suggesting that what you see will be what you get. Even for terrorists, the custodial element of a jail sentence will be two-thirds of the total instead of half.

For the most dangerous offenders, we are told, they will be expected to serve all of their sentence.

But the question is, will it work? Obviously terrorists in custody can’t launch more attacks so on a very basic level such a change could go some way towards preventing further bloodshed. But it is worth noting that recidivism is not a huge problem with terrorists.

Many who serve their sentences take it as a sign from God that they were not meant to go through with what they had planned. Some see the prison sentence as a trial of faith to test just how committed they are to the cause.

We do not know which of these Usman Khan was. He engaged with de-radicalisers in the year after his release from prison when there was no real incentive for him to do so. He appears to have been grateful to the Cambridge graduates who ran the de-radicalising scheme for raising money for a laptop – without access to the internet, to comply with his license conditions – and wrote them a poem in thanks.

Khan may have continued to harbour the same deep hatred for non-believers that he had before he went into jail or something may have re-ignited that hatred – his lawyer, Vajahat Sharif, who saw him before his release, suspects the second.

One of the questions for the new sentencing regime is whether there ought to be an incentive to co-operate with de-radicalisers in order to win the possibility of early release. That incentive would be one way of assessing if they still pose a serious risk after release and therefore merit close supervision.

But all terrorists are not created equal – some are propagandists and some are attack-planners, some run Twitter factories and some run bomb factories. Even among those planning attacks, one man may have searched online for a knife and mouthed off to his friend, another may have been mixing chemicals and visiting potential targets.

Those who work in prisons suggest that terrorists do turn their backs on their old ways and the statistics seem to back that up. Conflicts burn out, sources of anger evaporate, lives move on. Not for all, but for some, and we can encourage that process.

Talking to a de-radicaliser who understands both the social pressures that can push a young man – or sometimes woman – towards jihad, and the religious arguments they may have been exposed to online, may be able to help them turn a corner.

The government wants to do something to prevent terrorists using online services to ‘spread their vile propaganda and mobilise support’ and is seeking increased regulation of social media, video sharing, and instant messaging services. It is something that the families of the victims of the London Bridge and Westminster attacks of 2017, led by Gareth Patterson QC, called for during the inquests last year.

If the government can pull that off, it would certainly have the effect of dampening terrorist activity by cutting off their methods of pumping propaganda into the home – but it will be an uphill struggle.

Looking beyond these current government ambitions, there is a case for simplifying terrorist offences, which currently involve a number of anomalies. It is arguable that terrorism offences ought to include anyone who seeks to fight abroad in order to try and stop young people from freelancing in conflicts across the world. Last year the government introduced a new offence of visiting a ‘designated area’ but so far no areas have been designated.

The current legal definition of terrorism involves fighting against an established government, so travelling abroad to fight for one Islamist group against another is not a terrorist offence. Or indeed fighting for a neo-Nazi group against another militia in a country like Ukraine would not be included.

If you fight for a group backed by the UK government – including the Kurdish groups involved in the attempted overthrow of President Bashar al-Assad in Syria – you will not face prosecution, no matter how unhinged or violent you may be.

‘Indirectly’ encouraging acts of terrorism attracts a lower sentence than directly encouraging a single act, leaving preachers of violence to continue…