A philosopher once described European philosophy as essentially “a series of footnotes to Plato”; it would be no exaggeration to describe the hi

A philosopher once described European philosophy as essentially “a series of footnotes to Plato”; it would be no exaggeration to describe the history of political philosophy over the past half-century as a series of footnotes and responses to John Rawls.

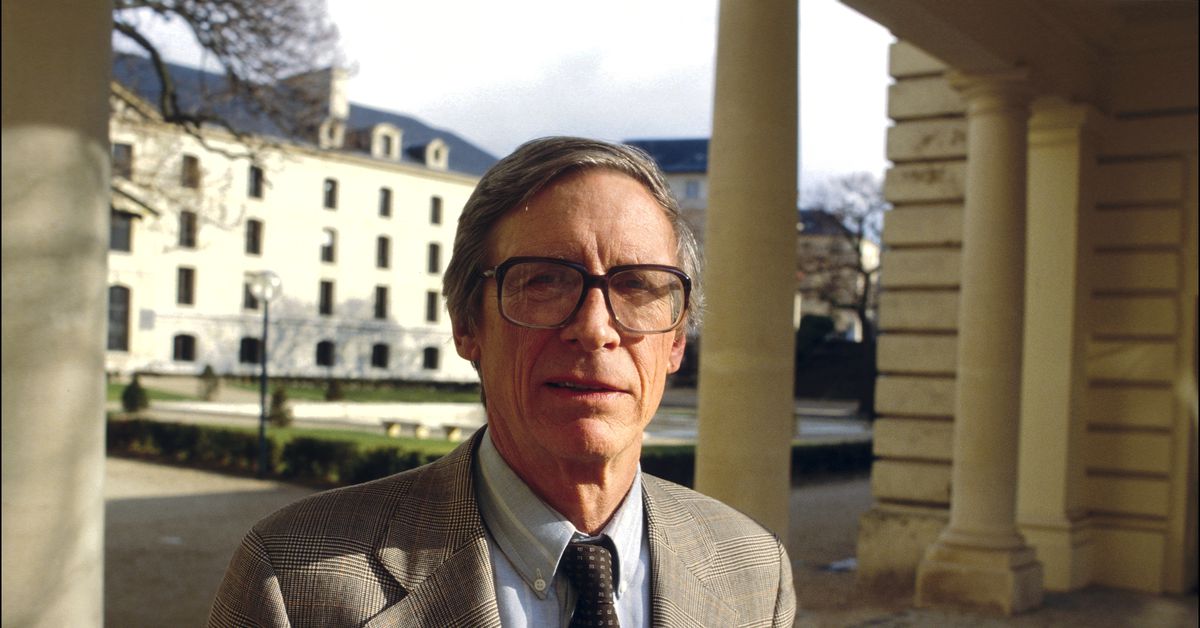

The Harvard philosopher looms over contemporary political thought, particularly on the left, in a way rivaled by no other scholar. When he died in 2002, one remembrance noted that over 3,000 articles specifically about Rawls had been published during his lifetime. A Theory of Justice, his most famous work, has been cited nearly 60,000 times by one metric. This year marks its 50th anniversary, with conferences on the occasion at University of Virginia Law School and Notre Dame.

The decades after the book’s publication were dominated by responses to Rawls and responses to responses to Rawls. Robert Nozick offered a libertarian rejoinder that nonetheless spoke Rawls’s language; Susan Moller Okin critiqued Rawls’s neglect of the family and gender inequality.

Charles Mills argued Rawls’s theory could not take white supremacy seriously as a political system. Tommie Shelby argued that it could. Tim Scanlon brought Rawlsian concepts to bear on individual ethics. Frank Michelman brought Rawls into the law. And so on, for thousands of books and articles.

That literature, in turn, has had profound influence on the wider world (Scanlon’s work even inspired a sitcom, of all things). But Rawls’s importance extends far beyond seminar walls and philosophy departments. His language and ideas have penetrated into political life, especially in the UK and US, because of their particular power in analyzing the deep economic inequalities that have grown in developed countries over the last few decades.

Fifty years on, Rawls’s most enduring legacy has been helping the generations that came after him make sense of what is unjust about a world characterized by both widespread destitution and outrageous wealth.

The veil of ignorance

Rawls’s key contribution was reviving the idea of a social contract, as detailed by philosophers like Hobbes, Locke, and Rousseau centuries before.

The principles of justice that should undergird a society and government, Rawls argued, are those set out in the social contract that members of society would hypothetically agree to behind a “veil of ignorance,” which prevents them from knowing what place in that society they would occupy.

The veil is key, because without it a straight white male aristocrat, safe in the knowledge that he would remain an aristocrat in the society he’s designing, would support a social contract with firm hierarchies, where he could continue to lord over his social lessers.

But if forced to consider the possibility that he might, instead, be a woman, or Black, or gay, or poor, he (and everyone else) would agree to different, fairer principles.

For Rawls, those principles were, in order, that 1) all people should be guaranteed equal basic liberties (to free speech, assembly, religion, etc.); and that 2) economic and social inequalities can exist, but only 2a) when compatible with equality of opportunity and 2b) when those inequalities help the least advantaged in society.

The difference principle

2b), better known as the “difference principle,” has become the dominant legacy of Rawls’s work, especially outside philosophy. It tries to avoid a more rigid egalitarianism, in which everyone’s economic outcomes must be equal, by allowing that some variation in resources can be just.

If the inventors of the Pfizer vaccine become billionaires in the context of helping the poorest people (in this instance, by helping save their lives), then that inequality can be justified. But if someone becomes a billionaire through rampant insider trading that has no benefit to the worst off, that cannot be justified.

As a matter of intellectual history, I think the prominence of the difference principle is slightly odd. Rawls himself argued that both basic liberties and equality of opportunity should take precedence over the difference principle, a point critics like Richard Arneson seized upon; if an aspect of society satisfied the difference principle but denied people equality of opportunity, that aspect of society was unjust, per Rawls. The difference principle plays a much less pronounced role in his theory than in its public reception.

But I think the difference principle’s endurance says something important about why Rawls has mattered.

Rawls and the New Gilded Age

A Theory of Justice was published just as the postwar liberal order in the US and UK was showing signs of strain. The efforts of leaders like Truman, Kennedy, Johnson, and (across the pond) Attlee and Wilson to build and sustain inequality-reducing welfare states were beginning to flounder.

The war in Vietnam had discredited Great Society liberalism among the young left, and, after Rawls’s book, the gas crisis and inflation would deal it a death blow and usher in Reagan and Thatcher.

Many have situated Rawls as an attempt to codify, with only light amendments, this kind of big-government, anticommunist postwar liberalism. Katrina Forrester’s book In the Shadow of Justice is the most nuanced version of this story I’ve seen; Forrester notes that Rawls “gave philosophers a distinctive structure of egalitarian thinking to defend against the libertarian threats to their right and to diffuse the promise of alternatives to their left.” Aaron Wildavsky, a right-leaning political scientist at Berkeley, was harsher, writing of Rawls and LBJ’s Great Society, “After the deed comes the rationalization.”

But as much as Rawls was looking back and refining the form of government that characterized the America and Britain where he had spent his adult life, he also, accidentally, wound up looking forward. He provided a language the left could use to describe what was wrong with the subsequent explosion of inequality in wealthy countries.

Relevantly, given that he did most of his work during the Cold War, Rawls’s language was non-Marxist. He did not write about class struggle or the power of the working class, much to the consternation of some of his colleagues.

But the difference principle provided a distinct way to argue against growing inequality in liberal, non-Marxist language. The problem wasn’t wealth and the existence of a capitalist class, per se. The problem was that this growing inequality provided no benefit, and indeed inflicted harm, on society’s least fortunate.

That has proven incredibly important as the wealth gap persists. It’s no accident that Bill Clinton honored Rawls at the White House, telling the audience, “when Hillary and I were in law school, we were among the millions moved by a remarkable book he wrote, A Theory of Justice.”

Barack Obama echoed him subtly but unmistakably in his speeches on income inequality and political tolerance.

I don’t want to credit too much of recent center-left politics to Rawls personally; there are probably a few campaign consultants with more influence. But as Marx before him demonstrated, giving people the language to understand what’s wrong with their society can be powerful.

Fifty years after Marx first published Das Kapital, the first Marxist state came into existence. Now, 50 years after A Theory of Justice, the book (and the backlash to its influence) stands ascendant as an animating intellectual force behind modern politics.

A version of this story was initially published in the Future Perfect newsletter. Sign up here to subscribe!

www.vox.com