WASHINGTON — One hundred million dollars for an airport in Mobile, Ala. Tens of thousands for upgrades to a police station in the tiny town of Milton,

WASHINGTON — One hundred million dollars for an airport in Mobile, Ala. Tens of thousands for upgrades to a police station in the tiny town of Milton, W.Va. Hundreds of thousands of dollars sent to Arkansas to deal with feral swine.

Stuffed inside the sprawling $1.5 trillion government spending bill enacted in March was the first batch of earmarks in more than a decade, after Congress resurrected the practice of allowing lawmakers to direct federal funds for specific projects to their states and districts. Republicans and Democrats alike relished the opportunity to get in on the action after years in which they were barred from doing so, packing 4,962 earmarks totaling just over $9 billion in the legislation that President Biden signed into law.

“It’s my last couple of years, so I decided to make the most of it,” said Senator Roy Blunt, Republican of Missouri and a member of the Appropriations Committee, who is retiring after more than two decades in Congress. He steered $313 million back to his home state — the fourth-highest total of any lawmaker.

Often derided as pork and regarded as an unseemly and even corrupt practice on Capitol Hill, earmarks are also a tool of consensus-building in Congress, giving lawmakers across the political spectrum a personal interest in cutting deals to fund the government. Their absence, many lawmakers argued, only made that process more difficult, and their return this year appears to have helped grease the skids once again.

“Earmarks can help members feel like they have a stake in the legislative process, in a legislative world where power is really centralized with party leaders,” said Molly E. Reynolds, a senior fellow in governance studies at the Brookings Institution. “They need some skin in the game, and earmarks — community project funding, whatever you want to call them — help members feel that efficacy and remind them why they came to Washington.”

The funding went to projects big and small, rural and urban, crustacean and porcine. Police departments across the country were awarded 75 earmarks — totaling nearly $50 million — while lawmakers steered money toward the National Atomic Testing Museum in Las Vegas, the Eternal Gandhi Museum in Houston and the Harry S. Truman Presidential Library and Museum in Independence, Mo., among other cultural institutions.

And then there were the animals. Beyond dealing with feral hogs, there was $569,000 for the removal of derelict lobster pots in Connecticut, $500,000 for horse management in Nevada, $4.2 million for improvements to the U.S. Sheep Experiment Station in Idaho and $1.6 million for equitable growth of the shellfish aquaculture industry in Rhode Island.

A review by The New York Times of the nearly 5,000 earmarks included in this year’s spending law revealed the following:

-

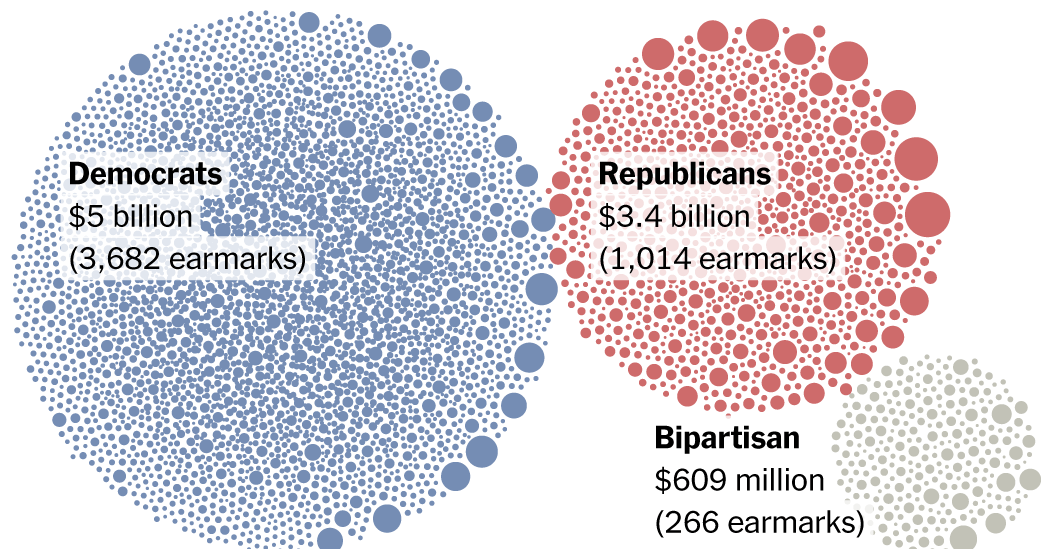

Overall, Democrats brought home considerably more money for their states than Republicans, some of whom boycotted the process. Democrats secured more than $5 billion for their states, compared with less than $3.4 billion for Republicans. Just over $600,000 of earmarks were bipartisan, secured by lawmakers in both parties.

-

The states that received the most money — California, Alabama, New York, South Carolina and Missouri — were either large and well-populated or had influential senators in leadership or on the committee that oversees spending.

-

Despite objections from many Republicans in Congress to earmarks, the few Senate Republicans who requested them racked up some of the biggest hauls, including Senator Richard C. Shelby of Alabama, the ranking member of the Appropriations Committee; Senator Lindsey Graham of South Carolina; and Mr. Blunt.

No one brought home more money than Mr. Shelby, who claimed credit for $551 million covering 16 projects, significantly more funding than any other lawmaker secured. He also had the single largest earmark: $132.7 million for the Alabama State Port Authority.

“I’m glad and proud of them,” said Mr. Shelby, a legendary pork-barreler who has no fewer than seven buildings named after him in Alabama. The latest spending package adds another, renaming a federal building and courthouse in Tuscaloosa for him.

“It’s a question of who do you want to do the earmarks,” he said. “You want the administration, the White House, to do them? Or do you want to do some yourself? They’re going to be done.”

Yet Congress had dealt itself out of the practice since 2011, when, following a series of scandals related to earmarks and an amid a wave of anti-spending fervor fueled by the Tea Party, lawmakers imposed a moratorium.

As Congress grew more partisan and dysfunctional in the years since, some lawmakers in both parties became convinced that reviving the practice — if made more transparent and subject to stricter rules — could help repair the institution.

Democrats announced this year that earmarks were back, now rebranded in the House as “community funding projects” and capped at 1 percent of the total spending appropriated. Requests had to be posted publicly online, with a letter explaining the need for the project. Each lawmaker had to sign a form attesting that they had no personal or family connection to it.

The limits were not enough for some lawmakers who were wary of the optics of claiming federal money for parochial goodies. Senator Jon Tester, Democrat of Montana, said he had refrained from requesting projects, despite his seat on the Appropriations Committee, because he had not had enough time to educate voters about the nuances of the process.

“There has to be some serious work done” to educate both lawmakers and voters, he said. “I just haven’t had the time to do that, so it’s just much easier for me not to ask for the earmarks.”

But those who availed themselves appeared unconcerned with appearances. Second in securing dollars was Mr. Graham, who brought home $361 million. In a statement, he challenged anyone who had an issue with one of his earmarks to take it up with him directly, noting that each was posted on his website.

“Every person will be able to judge for themselves if these are worthwhile requests,” he said.

Winning earmarks did not necessarily translate into support for the spending measure, particularly in the House, where it was split into two sections, defense and nondefense, and two separate votes were held.

Representative Elise Stefanik of New York, the No. 3 Republican, who claimed just under $35 million, voted against some of her own projects when she opposed the nondefense portion of the bill, which she said was filled with “far-left, partisan provisions.” Representative Mark Pocan, Democrat of Wisconsin, who secured $45 million, voted against the defense part of the legislation, which included an earmark he had helped secure; a spokesman said he did so because he opposed increasing military spending.

On the other side of the Capitol, Senator Bill Cassidy, Republican of Louisiana, secured $104 million in earmarks but still voted against the spending package, citing its omission of disaster aid for his state.

In the House, Representative James E. Clyburn of South Carolina, the No. 3 Democrat, said the funds he secured — nearly $44 million — included money to provide clean drinking water to poorer parts of his district.

“Nobody gives a damn about trying to make life better for these people — we’ve got communities where nobody can drink the water or can bathe in the water,” Mr. Clyburn said. “What are we going to do about it? And that’s what these projects are.”

Other lawmakers said they had gone to great lengths to ensure that the projects they funded would benefit as much of their state as possible.

Senator Kirsten Gillibrand, Democrat of New York, said she and her staff stuck pins in a state map to make sure there was a fair distribution of projects across counties and small towns.

“We wanted to visually really confirm that no part of the state was left out,” said Ms. Gillibrand, who secured about $231 million.

Representative Cheri Bustos, an Illinois Democrat who is retiring at the end of the year, brought home one of the highest dollar figures for any House member with more than $55 million, in part by partnering with lawmakers from both parties in her state’s delegation.

As she decided where the earmarks would go, she received input from 150 small towns in her district and evaluated the funding requests for merit and regional diversity. She then surveyed her husband and children to make sure none of them had a connection to any project.

“I would be even happier if we were No. 1,” Ms. Bustos said. “I’ve been in Congress for a little over nine and a half years now, and it makes me wish that we had been able to do this for the last nine and a half years.”

Earmarks have been a part of the federal budget since the early days of American democracy, but the practice rose in prominence as the size of the federal government grew, particularly amid a rise in taxes in the 1920s and 1930s.

After the Republican takeover of Congress in the 1990s, earmarks became a favorite punching bag, particularly amid high-profile scandals, including one involving Representative Randy Cunningham, Republican of California, who resigned in 2005 after pleading guilty to accepting at least $2.4 million in bribes.

Alaska became entangled in one such imbroglio when its notorious “bridges to nowhere” became symbols of fiscal waste.

But in a recent call with reporters, Senator Lisa Murkowski, Republican of Alaska, framed the $231 million in earmarks that she claimed this year as “Alaskan taxpayer dollars that are being returned to the state in ways that the communities have prioritized.”

Ms. Murkowski asked her staff to create an interactive map on her Senate website to track where each project was.

“I’m stressing this a little bit, because there are still some for whom ‘earmark’ is a four-letter word,” she said. “And I think it’s important, again, to recognize that there is a level of transparency now in this process that simply didn’t exist.”

About the Data

The Times summarized the total number and dollar value of earmarks included in the $1.5 trillion spending package using lists published by the House Appropriations Committee. The analysis includes earmarks obtained by members of the Senate and the House, including by nonvoting delegates to the District of Columbia and U.S. territories.

Dollar amounts assigned to individual members include the value of every earmark they signed onto, whether they requested them on their own or as a part of a group. The overall totals for Democrats include earmarks obtained by independents who caucus with them.

Rachel Shorey contributed reporting.

www.nytimes.com