John F. Banzaf III was watching soccer on tv together with his household within the Bronx on Thanksgiving 1966 when he realized that probably the m

John F. Banzaf III was watching soccer on tv together with his household within the Bronx on Thanksgiving 1966 when he realized that probably the most strategic performs have been being made off the sphere — within the cigarette commercials whose jingles, gags, slogans and pictures of virile cowboys and urbane ladies glamorized smoking.

Two years had elapsed since america surgeon normal declared that smoking prompted lung most cancers. However whereas Congress had voted to require well being warning labels on cigarette packaging, it had, in the intervening time, not required them for T.V. commercials.

Mr. Banzaf, a 25-year-old latest graduate of Columbia Legislation College, complained in a letter to the Federal Communications Fee that whereas tv information protection included each side of the tobacco debate, the cigarette commercials didn’t. Below the so-called equity doctrine, which required that each side of a difficulty of public concern be introduced, weren’t opponents of smoking entitled to free airtime?

“When his letter got here in, it struck a responsive chord, and I assumed why not use it?” Henry Geller, the F.C.C. counsel on the time, recalled in an unpublished memoir.

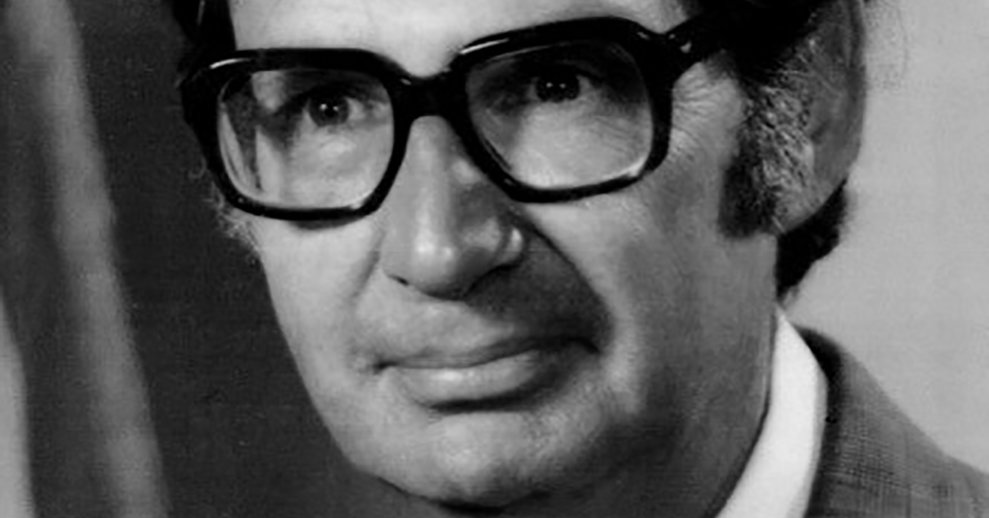

Mr. Geller, who died on April 7 in Washington at 96, did simply that. He steered that one antismoking public service message be broadcast free for each paid cigarette commercial.

That proposed components so unnerved station house owners afraid of jeopardizing their licenses, and tobacco firms involved about competing with highly effective antismoking commercials, that Congress was lastly capable of ban the promoting altogether.

“The business desperately wished to cease these counter advertisements and did so by eliminating its own ads,” Mr. Geller said. “From April 1, 1970, forward, all cigarette advertising was eliminated from radio and television.”

In effect, Mr. Banzaf said this week, “Geller fortuitously made new federal law in a most unusual manner, and probably helped to save millions of lives.” (Mr. Banzaf became a professor at George Washington University Law School and a litigious defender of public health, challenging cigarette, fast food and soft drink firms.)

Mr. Geller later profoundly influenced American politics by successfully challenging the fairness doctrine as a private citizen, a challenge that led to a ruling allowing for televised debates between the major presidential candidates. Such debates have been held in every presidential election since 1976.

In 1960, the networks had been granted a special dispensation by Congress to broadcast the groundbreaking face-off between Senator John F. Kennedy and Vice President Richard M. Nixon. Under the fairness doctrine, a dozen or so minor party candidates would have been entitled to participate in the debates.

After no televised debates were held in 1964, 1968 and 1972, Mr. Geller persuaded the commission that broadcasting debates was the equivalent of covering any other breaking news event and was therefore exempt from that requirement.

Unlike many of his colleagues in government, Mr. Geller never capitalized on his public service to get a high-paying job in the private sector. He worked for the RAND Corporation, the Aspen Institute and, from 1980 to 1991, Duke University’s Washington Center for Public Policy Research, where, as director, he helped draft and successfully lobby for federal legislation that imposed limits on how much advertising was allowed on children’s programming.

Henry Geller was born on Feb. 14, 1924, in Springfield, Mass., to Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe. His father, Samuel, was a homebuilder. His mother, Sadie (Kramer) Geller, was a homemaker.

He grew up in Detroit and, after graduating from the University of Michigan at 19 in 1943 with a degree in chemistry, served with the Army in the Pacific during World War II. When he returned, he began graduate study in chemistry at Michigan. But, he later recalled, when he encountered several law school students and learned that they rarely studied, he enrolled in Northwestern University School of Law.

“I thought Henry was the smartest guy in law school,” Newton N. Minow, who was a year behind him at Northwestern and who later became F.C.C. chairman, told Broadcast magazine in 1979. “He was a movie nut. He’d go to three movies a day and never hit the books until a week before exams.”

Mr. Geller graduated second in his class in 1949, went to work for the F.C.C. and then for the National Labor Relations Board, and clerked for an Illinois state judge.

In 1955 he married Judy Foelak, who ran a speakers’ bureau. She survives him and confirmed his death, from complications of bladder cancer, at their home in Washington. He is also survived by their children, Peter Geller and Kathryn Edwards, and a grandson.

Mr. Geller was the F.C.C.’s general counsel from 1964 to 1970 and a special assistant to the chairman until 1973. From 1978 to 1980, he was the first administrator of the National Telecommunications and Information Administration.

He remained current on evolving technology; not long ago he said he was trying to figure out how to persuade Congress to mandate attribution for online political advertising.

A rumpled man with a preference for sneakers and jeans, he played tennis into his 90s, taught himself quantum physics and could argue a complex case without a single note. He preferred movies to television — which, borrowing from Frank Lloyd Wright, he referred to as “chewing gum for the eyes” — and, when he did tune in, usually confined himself to nature documentaries or quirky British comedy like “Monty Python’s Flying Circus.”

Mr. Geller was that rare former public official who could not only laugh at himself but also admit a mistake — such as when he advised Mr. Minow, the newly installed F.C.C. chairman, against using what would become his signature phrase.

In a scathing speech to the National Association of Broadcasters in 1961, Mr. Minow praised good television but challenged broadcast executives to spend a full day in front of their sets without any distraction. “What you will observe,” he said, “is a vast wasteland.”

“I told him not to say it,” Mr. Geller recalled in an oral history interview for the Fordham University Libraries in 2010. “I said, ‘You have every right to say they’re not delivering public service, but you shouldn’t go around on the quality of programs.’ The government can’t do quality. It’s subjective. It violates the First Amendment.”

“He laughs now,” Mr. Geller continued, “and he always introduces me saying, ‘This is the man who told me not to say vast wasteland.’”