This text was produced in partnership with the Pulitzer Middle on Disaster Reporting.WASHINGTON — With the coronavirus pandemic additional isolatin

This text was produced in partnership with the Pulitzer Middle on Disaster Reporting.

WASHINGTON — With the coronavirus pandemic additional isolating the jail at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, the Trump administration is coming beneath growing strain to seek out methods to let probably the most remoted males among the many 40 wartime prisoners talk with their attorneys.

Solely one of many 5 males accused of plotting the Sept. 11, 2001, assaults has thus far been in a position to communicate together with his lawyer throughout the pandemic, by a particular video hyperlink between a Pentagon constructing outdoors Washington and the courtroom at Guantánamo.

Then on Friday, a federal decide ordered the Justice Division to report again in 30 days on how one other prisoner — a Somali man who has by no means been charged with against the law — may maintain a labeled cellphone name together with his lawyer.

Decide Reggie B. Walton of the USA District Court docket in Washington set the deadline in a standing convention by phone within the case of Guled Hassan Duran, 46, a Somali man, who’s in search of launch by a federal habeas corpus petition. Mr. Duran, who’s recognized in navy data as Gouled Hassan Dourad, was captured in Djibouti in 2004 and has been at Guantánamo since 2006.

At issue is how to balance the insistence of the defense lawyers that they continue to consult with their clients, even as some proceedings are delayed because of the pandemic, and the insistence of the government that 14 of the 40 men held at Guantánamo could disclose classified information if they were allowed routine telephone calls.

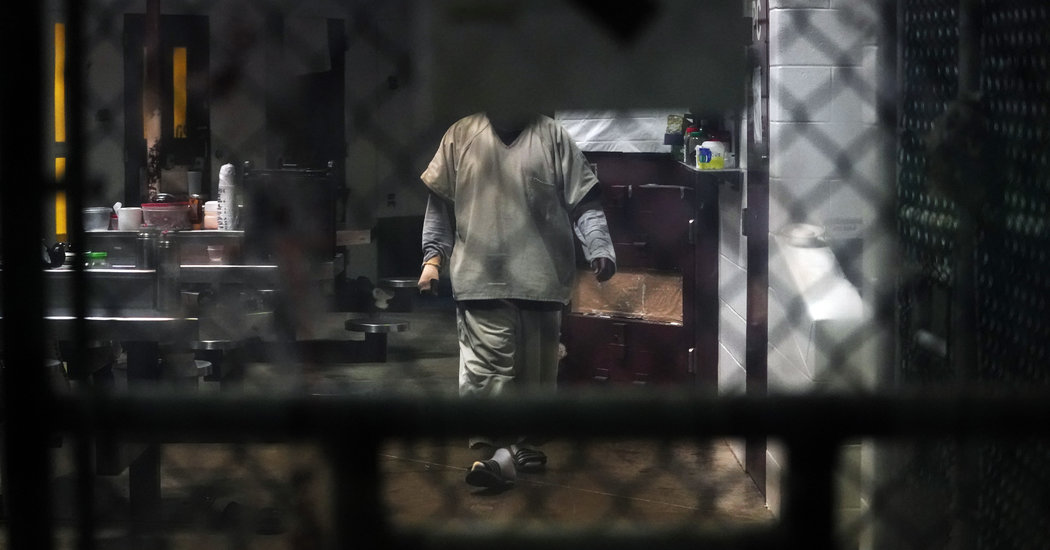

Those 14 prisoners were held at secret C.I.A. sites before their transfer to Guantánamo more than a decade ago. The intelligence agencies argue that they continue to know national security secrets, including where they were held and perhaps the identities of their captors. They are only allowed written communications through secure channels with their lawyers when the lawyers are not at Guantánamo.

The other 26 prisoners held at Guantánamo have been able to speak with their lawyers by telephone for years, including throughout the public health crisis.

Lawyers representing the prisoners regularly visit the base during normal times, but those trips came to a halt in March, after the military discontinued its weekly legal shuttles there because of the pandemic and limited travel to essential personnel. The prison also adopted a policy of requiring lawyers to isolate themselves for two weeks on the base, once legal visits are restored.

Among those most directly affected are the five defendants accused of helping plot the Sept. 11 attacks. Prosecutors in that case proposed one-hour weekly video chats between the defendants and their lawyers linking two classified facilities — a teleconference suite at military commissions headquarters in Alexandria, Va., and the courtroom at Camp Justice at Guantánamo.

The chief war court judge, Col. Douglas K. Watkins, has ordered prosecutors in the Sept. 11 case to explain why the defendants cannot get the same telephone calls as other prisoners.

Only one lawyer in the case has used the war court teleconference facilities. Walter B. Ruiz, the capital defender for Mustafa al Hawsawi, said on Friday that his conversation with his client lasted two hours on Wednesday — with mixed results.

The camera angle made it impossible to see and discuss documents Mr. Hawsawi had at the defense table in front of him, Mr. Ruiz said.

Mr. Ruiz said he and two linguists on their side of the video conference had to huddle — closer than the six-foot distance mandated under social-distancing guidelines — to see and be seen. But the prisoner, he said, “seemed to be in good spirits.”

Mr. Hawsawi appeared on camera in a beige cloth mask, which he removed for the meeting. Soldiers serving as guards wore gloves, masks and plastic face shields.

“The most practical and adequate thing is to go down to the jailhouse and sit down face to face and go over documents,” Mr. Ruiz said. “That is the standard that we should have. But given the circumstances, I like being able to see each other.”