Each spring, British college students take their A-level exams, that are used to find out admission into faculty.

However this yr was completely different. With the Covid-19 pandemic nonetheless raging, spring’s A-levels had been canceled. As a substitute, the federal government took an unorthodox — and controversial — method to assessing admissions with out these examination scores: It tried to make use of a mathematical rule to foretell how the scholars would have performed on their exams after which use these estimates as a stand-in for precise scores.

The method the federal government took was pretty easy. It wished to guess how properly a scholar would have performed if they’d taken the examination. It used two inputs: the coed’s grades this yr and the historic monitor file of the varsity the coed was attending.

So a scholar who received wonderful grades at a college the place high college students normally get good scores can be predicted to have achieved an excellent rating. A scholar who received wonderful grades at a college the place wonderful grades traditionally haven’t translated to top-tier scores on the A-levels would as a substitute be predicted to get a decrease rating.

The general consequence? There have been extra high scores than are awarded in any yr when college students really get to take the examination.

However many particular person college students and lecturers had been nonetheless indignant with scores that they felt had been too low. Even worse, the adjustment for a way properly a college was “anticipated” to carry out ended up being strongly correlated with how wealthy these faculties are. Wealthy youngsters are likely to do higher on A-levels, so the prediction course of awarded youngsters at wealthy faculties increased grades.

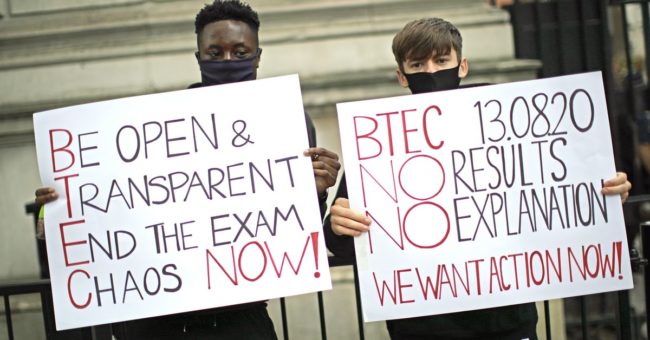

The predictive course of and its consequence set off alarm bells. One Guardian columnist known as it “shockingly unfair.” Authorized motion was threatened. After a weekend of indignant demonstrations the place college students, lecturers, and fogeys chanted, “Fuck the algorithm,” Britain backed off and introduced that it’ll give college students no matter grade their lecturers estimated they might get if it’s increased than the examination rating estimates.

What’s taking part in out in Britain is a bunch of various issues directly: a drama introduced on by the Covid-19 pandemic exacerbated by dangerous administrative decision-making in opposition to the backdrop of sophistication tensions. It’s additionally an illustration of an interesting dilemma usually mentioned as “AI bias” or “AI ethics” — regardless that it has virtually nothing to do with AI. And it raises essential questions concerning the sort of biases that get our consideration and those who for no matter motive largely escape our scrutiny.

Predicting an unfair world

Think about a world the place wealthy youngsters and poor youngsters are simply as more likely to do medication, however poor youngsters are 5 instances extra more likely to be arrested. Each time somebody is arrested, a prediction system tries to foretell whether or not they’ll re-offend — that’s, whether or not somebody like that particular person who’s arrested for medication will doubtless be arrested for medication once more inside a yr. If they’re more likely to re-offend, they get a harsher sentence. If they’re unlikely to re-offend, they’re launched with probation.

Since wealthy youngsters are much less more likely to be arrested, the system will accurately predict that they’re much less more likely to be re-arrested. It can declare them unlikely to re-offend and advocate a lighter sentence. The poor youngsters are more likely to be re-arrested, so the system tags them as doubtless re-offenders and recommends a harsh sentence.

That is grossly unfair. There isn’t any underlying distinction in any respect within the tendency to do medication, however the system has disparities at one stage after which magnifies the disparities on the subsequent stage through the use of them to make legal judgments.

“The algorithm shouldn’t be predicting re-jailing; it needs to be predicting re-offending. However the one proxy variable we’ve for offending is jailing, so it finally ends up double-counting anti-minority judges and police,” Leor Fishman, a knowledge scientist who research information privateness and algorithmic equity, advised me.

If the prediction system is an AI skilled on a big dataset to foretell legal recidivism, this drawback will get mentioned as “AI bias.” However it’s straightforward to see that the AI isn’t really an important element of the issue. If the choice is made by a human choose, going off their very own intuitions about recidivism from their years of legal justice expertise, it’s simply as unfair.

Some writers have pointed to the UK’s college selections for example of AI bias. However it’s really a stretch to name the UK’s Workplace of {Qualifications} and Examinations Regulation’s method right here — taking scholar grades and adjusting for the varsity’s previous yr’s efficiency — an “synthetic intelligence”: it was a simple arithmetic method for combining just a few information factors.

Reasonably, the bigger class right here is maybe higher known as “prediction bias” — circumstances the place, when predicting some variable, we’re going to find yourself with predictions which are disturbingly unequal. Typically they’ll be deeply influenced by elements like race, wealth, and nationwide origin that anti-discrimination legal guidelines broadly prohibit taking into consideration and that it’s deeply unfair to carry in opposition to individuals.

AIs are only one device we use to make predictions, and whereas their failings are sometimes notably legible and maddening, they aren’t the one system that fails on this method. It makes nationwide information when a husband and spouse with the identical earnings and debt historical past apply for a bank card and get provided wildly completely different credit score limits due to an algorithm. It in all probability received’t be observed when the identical factor occurs however the resolution was made by an area banker not counting on complicated algorithms.

In legal justice, specifically, algorithms skilled on recidivism information make sentencing suggestions with racial disparities — as an illustration, unjustly calling to imprison Black males for longer jail time than white males. However when not utilizing algorithms, judges make these selections off sentencing tips and private instinct — and that produces racial disparities, too.

Are disparities in predictions actually extra unjust than disparities in actual outcomes?

It’s essential to not use unjust techniques to find out entry to alternative. If we try this, we find yourself punishing individuals for having been punished up to now, and we etch societal inequalities deeper in stone. However it’s value eager about why a system that predicts poor youngsters will do worse on exams generated a lot extra rage than the common system that simply administers exams — which, yr after yr, poor youngsters do worse on.

For one thing like college examination scores, there aren’t disparities simply in predicted outcomes however in actual outcomes too: Wealthy youngsters usually rating higher on exams for a lot of causes, from higher faculties to raised tutors to extra time to check.

If the examination had really occurred, there can be widespread disparities between the scores of wealthy youngsters and poor youngsters. This may anger some individuals, however it doubtless wouldn’t have led to the widespread fury that comparable disparities within the predicted scores produced. In some way, we’re extra snug with disparities once they present up in precise measured check information than once they present up in our predictions about that measured check information. The fee to college students’ lives in every occasion is identical.

The UK successfully admitted, with their check rating changes, that many youngsters within the UK attended faculties the place it was very implausible they might get good examination scores — so implausible that even the actual fact they received wonderful grades all through college wasn’t sufficient for the federal government to anticipate they’d discovered every little thing they wanted for a high rating. The federal government might have backed down now and awarded them that high rating anyway, however the underlying issues with the colleges stay.

We should always get critical about addressing disparities once they present up in actual life, not simply once they present up in predictions, or we’re pointing our outrage on the flawed place.

New objective: 25,000

Within the spring, we launched a program asking readers for monetary contributions to assist hold Vox free for everybody, and final week, we set a objective of reaching 20,000 contributors. Nicely, you helped us blow previous that. At the moment, we’re extending that objective to 25,000. Tens of millions flip to Vox every month to know an more and more chaotic world — from what is going on with the USPS to the coronavirus disaster to what’s, fairly probably, probably the most consequential presidential election of our lifetimes. Even when the financial system and the information promoting market recovers, your help can be a essential a part of sustaining our resource-intensive work — and serving to everybody make sense of an more and more chaotic world. Contribute at present from as little as $3.