“Did I make over a million dollars this year? Yes I did.”Joshua Davis is among hundreds, maybe thousands, of creators who have made life-changing a

“Did I make over a million dollars this year? Yes I did.”

Joshua Davis is among hundreds, maybe thousands, of creators who have made life-changing amounts of money from the non-fungible token (NFT) boom. But he didn’t make his mil selling profile jpegs of zombie gophers wearing polo shirts.

This feature is part of CoinDesk’s Culture Week.

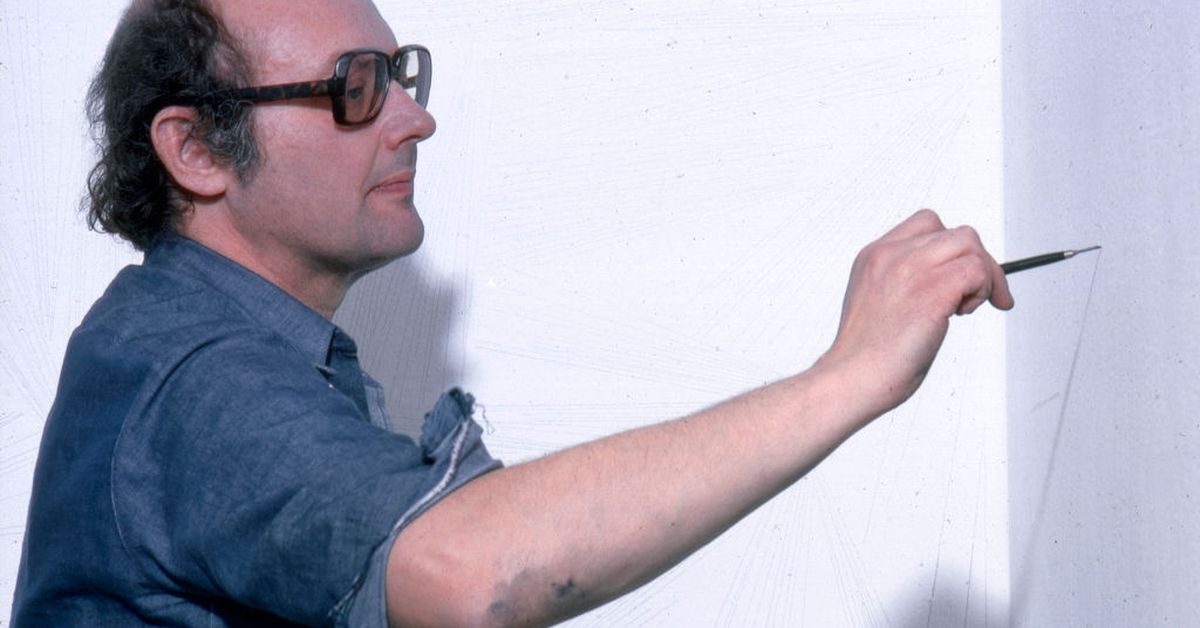

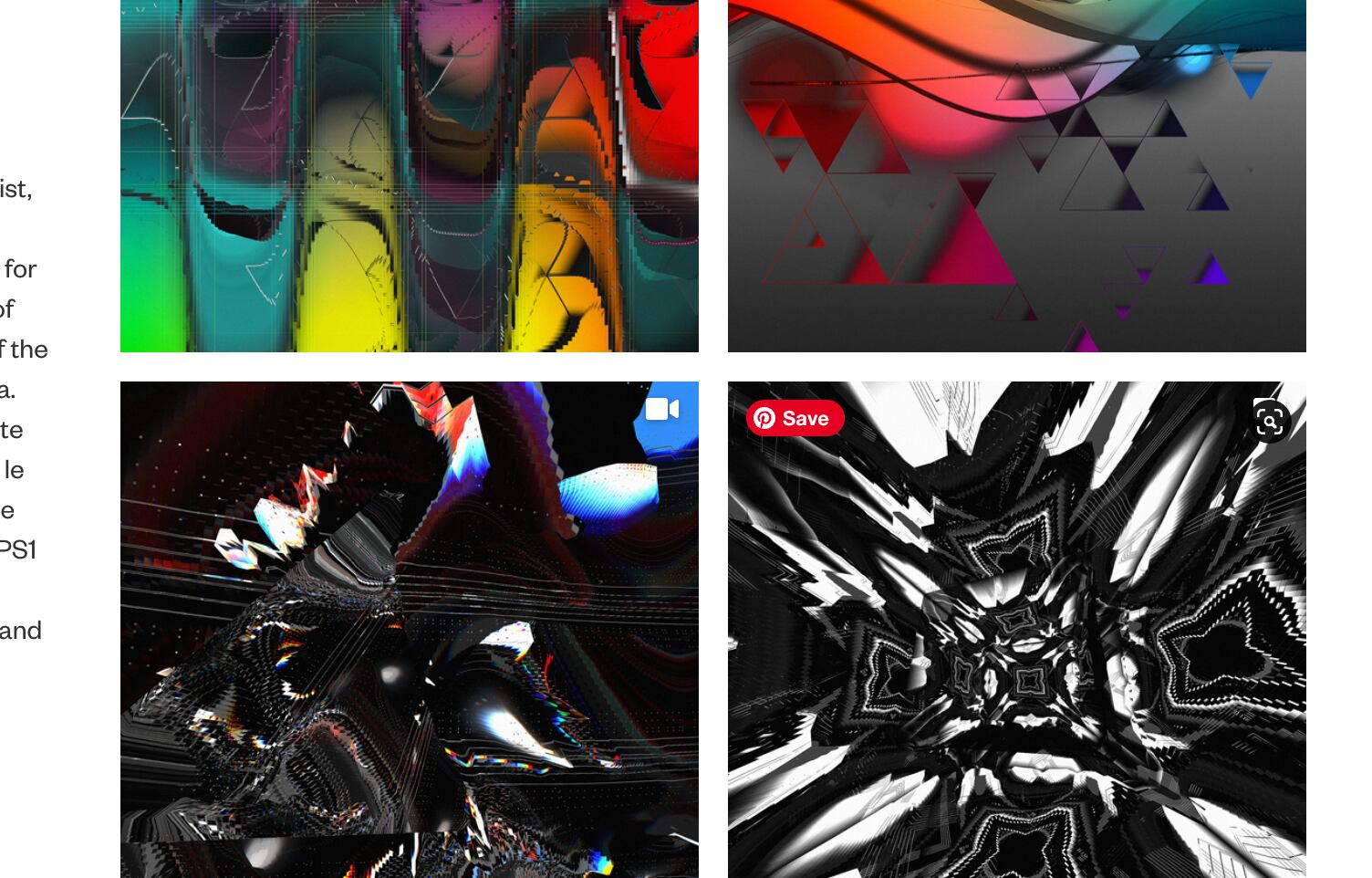

Davis founded Praystation.com in 1995 to display his art, part of a new wave of creativity then being unleashed by home computers and the World Wide Web. His works, at first composed largely using the Flash animation tool, consist of code that produces dozens, even hundreds, of related images by repeating a set of rendering commands, with randomly changing variables for features like color and line length.

The images are abstract, noisy, sometimes unnerving. Davis’ work made him a respected digital artist decades before the first Ape got Bored, and one of the contemporary scions of “generative art,” an artistic tradition whose roots stretch back at least as far as the 1940s. In its modern form, generative art weds computer science with biology and physics to create images, sound or video based on randomized elements and parameters. The results are often fascinating, and just as often deeply strange.

But for decades, Davis and his contemporaries struggled with a very real problem: money. Because their art was nothing more than bits, there was no individual, unique object they could sell in the way one would a painting. Artists like Davis have sold prints and books, but they largely missed out on the kind of big collector paydays that other leading fine artists enjoy. That is, until NFTs came along.

“I never thought this would happen in my lifetime,” Davis says of NFT technology and its huge benefits for generative art. “I thought the next generation maybe would find a way to find value in digital art. I never thought digital art would be embraced as something you could assign provenance, collectability and scarcity.”

While headlines have focused on the speculative, trivial, sometimes silly applications of NFTs, the technology has truly transformed Davis’ very respectable corner of the art world. They’re giving an entire artistic tradition that had been ephemeral and conceptual the chance to join the fine art market on solid footing for the first time.

What is generative art?

If you’re an NFT fan, you might have heard the term “generative art” applied to “profile pic” NFTs like those Bored Apes, whose features are randomly selected based on a “rarity” algorithm. That makes Pudgy Penguins and Wonky Whales, believe it or not, descendants of path-breaking work by some of the most important artists of the 20th century.

In my conversations with generative artists working today, one name came up again and again as a touchstone: Sol LeWitt. Starting in the late 1960s, LeWitt began producing large, geometrical wall drawings, not by drawing them himself but by writing detailed instructions that could be executed by anyone. Galleries still regularly present the works as interactive collaborations, with viewers themselves doing the drawing.

Joshua Davis says his “aha” moment as an artist was realizing the same logic could be applied more generally. “When an artist walks in front of a blank canvas, there are decisions that are made – the colors I use, the brush, the canvas, the kind of strokes I’m going to make … I could look at [Jackson] Pollock or [Jean-Michel] Basquiat – here are the kinds of strokes, the actions. Those actions, I could program.”

Other mid-century artists helped lay the foundations for generative art by taking cues from then-emerging computer technology. The Hungarian-French designer Victor Vasarely crafted rigid grids and 3D illusions that predated computer graphics by as much as half a century. The Dutch designer Karel Martens produced dozens of iterative sets of overlapping shapes. Among the first artists to actually apply a computer to art making was Grace Hertlien, who said other artists called her a “whore” and a “traitor” for using computational processes in art.

Other prominent creatives were exploring ideas of procedure and randomness alongside these visual pioneers. Starting in the mid-1940s, composer John Cage and choreographer Merce Cunningham began using “chance operations” such as flipping a coin to determine the length of a note. In the 1950s, the painter Brion Gysin and novelist William Burroughs developed the “cut up” method of generative writing, which produced new work by cutting up existing text and randomly rearranging it. (Burroughs was also strangely connected to early computing, as the heir of an adding machine empire).

These pathways represent the two big ideas being explored in generative art: chance and systems design. John Cage often subtracted his own intention from his work as a challenge to the romantic notion of artistic genius, as with his infamous “4:33″ – a…

www.coindesk.com