Courtesy of TIFF It has been nearly 27 years since Tupac Shakur was murdered, meaning that the hip-hop icon has been gone for lo

Courtesy of TIFF

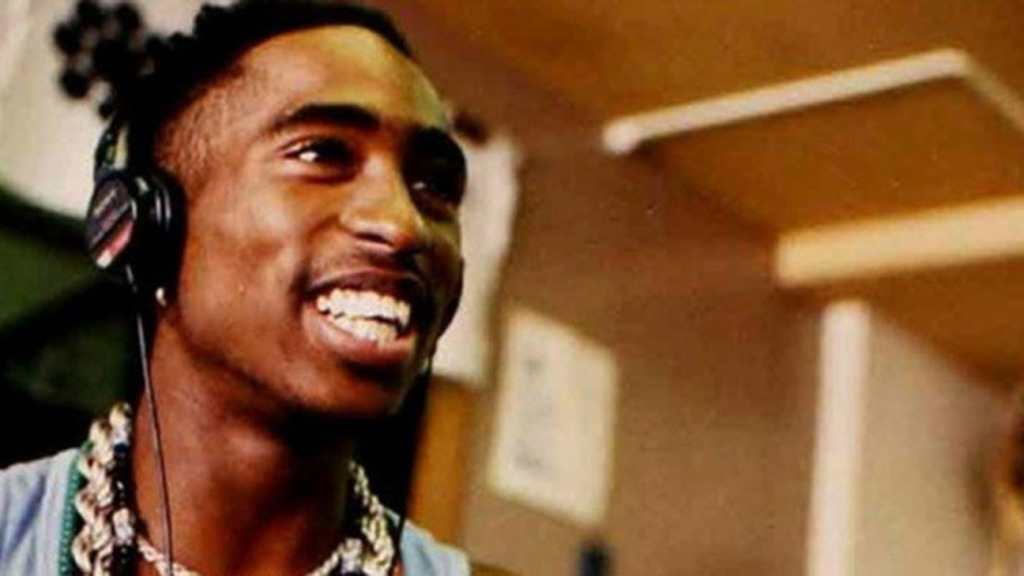

It has been nearly 27 years since Tupac Shakur was murdered, meaning that the hip-hop icon has been gone for longer than the 25 years he walked the earth. At this point, as we’re in our third decade of mythologizing every aspect of his brief life, chances of fully extricating the truths about Tupac from various tall tales are low.

Allen Hughes’ new FX documentary Dear Mama at least has a coherent, ambitious and sometimes productive approach. At five hours (and then-some), the series feels overstuffed, albeit in a way that mirrors its prolific subject, and some of its connective swings are misguided at best. But Dear Mama has some real insights into the intersection of Black activism and popular music in the late 20th century.

Dear Mama

The Bottom Line

Tackles the contradictions of its subject in a fruitful way.

Airdate: 10 p.m. Friday, April 21 (FX)

Director: Allen Hughes

Hughes’ approach, one that has been taken before in Tupac scholarship but surely not at this depth, is to directly parallel the lives of Tupac and his mother Afeni Shakur.

Dear Mama doesn’t quite have a 50-50 split in its focus, but even giving Afeni Shakur 30 percent of the screentime here produces interesting results. Afeni was a leader in the Black Panther Party, spending much of her pregnancy with the future music superstar in prison as one of the so-called Panther 21. With no legal training, she represented herself in court. In some circles she was a feminist standard-bearer and she was a key figure in fighting homophobia in her movement (a side of her biography that goes completely unmentioned in Dear Mama). She battled addiction and, with her years of financial difficulties, she continually uprooted her family and contributed to the displacement that shaped her son’s psyche, not always in positive ways.

As Glo, Tupac’s aunt and Afeni’s sister, puts it in the documentary, “Where did Tupac get the myth-building from? Afeni. And ‘Feni wanted the story told. Correctly. That means blemishes and all, so people can understand that whole thing of what makes a human being.”

With that as an aspiration, and Glo as one of its most dynamic and endearing legacy caretakers, Dear Mama comes very close at times. It’s still hung up on a certain amount of hagiography for both mother and son, but it’s a sort of blemishes-and-all hagiography, an attempt to juxtapose their aspirations and reconcile their contradictions.

The attempt is what Dear Mama does best. Hughes and editor/co-writer/producer Lasse Järvi have made a documentary that’s five hours of grappling, since there’s no concrete “solution” to the mysteries of Tupac.

Was he an artist praised for his authenticity who, at the same time, came from a performing background and viewed his public persona as another character to play? Absolutely. Was he a fierce respecter of women who ran through a long series of partners and spent time in jail for a crime of sexual violence? Yes. Did he become increasingly out of control as his visibility increased? Or did he realize that giving the impression of being out of control added to his visibility and his public platform?

And speaking of that platform, was his music a gateway to acting aspirations? And were both just ways of setting himself up for a future in politics or something in that vein? Was he a compulsive workaholic because he had so much inside that he needed to get out, or just because he suspected his lifespan was finite and he wanted to do as much as he could in the limited time he expected to have? There are no answers to all these questions, but Dear Mama wants to make sure you’re pondering them through the entire documentary.

Certainly, nobody appearing on-camera here has answers. Hughes converses with family members, parts of his professional team and collaborators from every phase of his career, from Snoop Dogg to the late Shock G to Gridlock’d co-star Tim Roth. The talking heads care deeply about Tupac and are protective of Tupac and, decades later, remain in awe of Tupac, but what they offer is loving data points more than insights.

The insights come from the way the filmmakers attempt to put the film together, eschewing a conventional, linear narrative in favor of placing events from Afeni’s life — various Panthers colleagues speak of her with an awe that mirrors the way people speak of her son — with pieces from his journey.

Sometimes the result is messily provocative. The fourth episode interweaves Afeni’s post-prison struggles with Tupac’s increasingly compulsive and self-destructive tendencies after his own incarceration, raising thoughts about inherited trauma and rehabilitation. There is nothing concrete directly connecting these personal arcs, nobody to speak to conversations between the two Shakurs, but the ideas are enough to be worthwhile.

And sometimes the result is messily infuriating. The third episode juxtaposes Afeni’s trial with Tupac’s New York City sexual assault trial in a way that only makes sense if you think being a political prisoner of the U.S. government is identical to the charges that Tupac was facing.

Just as fans haven’t always known how to handle the violent chapters in Tupac’s life, the documentary struggles there as well. The shooting of two off-duty cops in Atlanta actually opens the series and is treated as a thing of legend, more significant for its ties to the debut of “Dear Mama” (the indelible song) than as a crime. The Quad Studios shooting is rushed through, more notable for how Tupac eventually recovered in Jasmine Guy’s home, part of an intriguing family relationship — Guy wrote Afeni’s autobiography — that the documentary doesn’t really explain. The documentary repeatedly scoffs at any rivalry between Tupac and Biggie, much less any connections between their murders, giving the impression of protesting too much, methinks. Suge Knight is a menacing off-screen force, spoken of evasively and tentatively by folks like Snoop Dogg and Dr. Dre.

Notably, the person with the most direct tie to Tupac at his worst might be Hughes himself. After directing multiple early Tupac videos, Hughes removed Shakur from Menace II Society, instigating an assault that Tupac did time for.

“For the record, Tupac didn’t beat me up. Ten other motherfuckers did,” Hughes tells Snoop from behind the camera, part of a long, filmed debate over how much Hughes should be a character in his own documentary. The answer turns out to have been “some,” but even after taking a seat in front of the camera, Hughes becomes just another of those data points, somebody able to say what happened to him without fully making sense of it. Tupac was a friend who was crucial to the early stages of Allen Hughes’ career and Tupac — or “10 other motherfuckers” in Tupac’s crew — beat Allen Hughes to a pulp. Again, it’s the grappling that’s important and not the resolving.

Sometimes the non-chronological approach makes the documentary feel like it’s racing along too quickly, skipping key details. Other times, the circling back on itself makes the documentary feel like it’s being repetitious and wallowing. Sometimes it feels like it’s critiquing the hip hop landscape of the ’90s, with its binary between gangsta rap and party anthems; other times it feels like it’s lionizing that cultural moment and casting judgment on what was real and what was artificial.

Sometimes Tupac’s music gets lost or becomes an afterthought, and then you’ll get an unseen performance that reminds you, “Oh right, the guy was some sort of genius.” Sometimes the documentary is on the verge of losing track of Afeni entirely and then it re-centers around a speech or appearance that has a potency all its own. Dear Mama is challenging and not always successful, but the challenges feel right for the subject.

www.hollywoodreporter.com