Paul H. O’Neill had simply presided over a celebrated revival of the aluminum large Alcoa and was about to start his retirement in late 2000 with a

Paul H. O’Neill had simply presided over a celebrated revival of the aluminum large Alcoa and was about to start his retirement in late 2000 with a protracted drive throughout the again roads of America in a brand new Bentley Flying Spur.

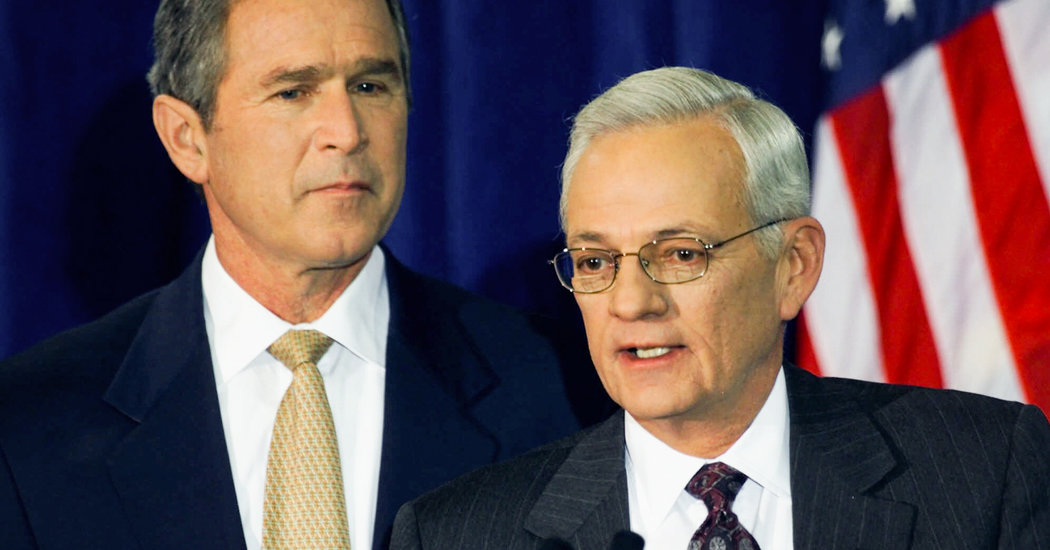

Then got here calls from Vice President-elect Dick Cheney asking him to turn into secretary of the Treasury. Regardless of having a listing of causes for being not proper for the job — a key one being that he had turn into used to being the boss — Mr. O’Neill agreed.

It turned out to be an agonizing tenure.

Mr. O’Neill lasted lower than two years within the job; his outspoken independence was seen as political disloyalty, and President George W. Bush fired him in December 2002.

On Saturday, Mr. O’Neill died at his dwelling in Pittsburgh at 84. His son, Paul Jr., stated the trigger was lung most cancers.

Having been handed his strolling papers by the White Home, Mr. O’Neill rejected the suggestion that he ought to say publicly that he needed to return to non-public life.

“I’m too outdated to start telling lies now,” he stated with typical candor. “If I took that course, individuals who know me nicely would say that it wasn’t true. And individuals who don’t know me nicely would say, ‘O’Neill was a coward — issues aren’t going so nicely, and he bailed out on the president.’”

He promptly grew to become the topic and chief supply for a uncommon e-book in regards to the interior workings of an administration nonetheless in energy, “The Value of Loyalty: George W. Bush, the White Home, and the Training of Paul O’Neill,” by Ron Suskind, revealed in 2004. Its contents had been thought-about so politically risky at a time when Mr. Bush was looking for re-election that the title was withheld till simply earlier than publication.

Mr. Suskind referred to as the e-book “an experiment in transparency,” counting on 1000’s of paperwork provided by Mr. O’Neill, who fact-checked the manuscript. Michael Tomasky, writing in The New York Occasions E-book Assessment, stated it confirmed how “deeply corrupted” traditions of public service had turn into. The e-book reached No. 1 on The Occasions’s best-seller listing.

Amongst its allegations was not solely that Mr. Bush was typically unengaged in coverage discussions, but additionally that many selections, together with the invasion of Iraq, had appeared to have been politically ordained.

As Mr. Bush’s agency time period proceeded early on, the impression grew amongst outsiders that Mr. O’Neill’s lengthy company profession had rendered him insensitive to Washington realities and undermined his affect.

“Folks assume he was politically tone-deaf,’’ David Aufhauser, the final counsel of the Treasury Division from 2001 to 2004, was quoted as saying within the e-book. “He wasn’t.”

“He knew full nicely the political penalties,” Mr. Aufhauser stated, and he was “fearless” in urgent concepts based mostly on information and proof. He cautioned, for instance, that Mr. Bush’s tax cuts had been ill-advised. In earlier authorities stints, Mr. O’Neill had been concerned in issues starting from tax coverage, well being care and welfare reform to meals stamps, busing and housing.

In reality, Mr. O’Neill famous in an interview for this obituary in 2017, his Washington expertise had been “greater than that of anyone on the desk.” That have included intimate involvement in many of the main home controversies of the Nixon years as a high-ranking official on the Funds Bureau. (It was renamed the Workplace of Administration and Funds throughout his tenure, which included appointment as deputy director.)

He and three others on the finances workplace — Roy L. Ash, Frederic V. Malek and Frank G. Zarb — were reported to have largely run the government in 1974 at a time when President Richard M. Nixon was weakened by the Watergate scandal.

“That’s basically correct,” Mr. Zarb, a longtime friend of Mr. O’Neill’s, recalled many years later. Mr. O’Neill, he said, “knew more about government life than most people in government.”

Mr. O’Neill acknowledged that he had misjudged the influence he could have in the Bush administration. “I thought I knew the players well enough, and that we were like-minded about fact-based policymaking,” he said. “It turned out that was all wrong.”

Paul Henry O’Neill was born on Dec. 4, 1935, in St. Louis into a military family and grew up on bases in the Midwest and West with his two brothers and a sister. His father, John Paul O’Neill, was a master sergeant in the Army Air Forces. His mother was Gaynold (Irving) O’Neill.

He attended Anchorage High School in Alaska, where he met Nancy Wolfe. They married in 1955. She survives him, as do his son; three daughters, Patricia Wilcox, Margaret Tatro and Julie Kloo; 12 grandchildren; and 15 great-grandchildren.

Mr. O’Neill enrolled at California State University, Fresno, with ambitions to be an engineer but left for a time to take road survey and site engineering jobs in Alaska. When he returned to Cal State, he graduated in three years. It was there, he said, that he “decided that economics was a lot more interesting than engineering.”

Changing course, he began a five-year doctoral program in economics at Claremont Graduate University in Pomona. While there, on a lark, he took an exam for midlevel government jobs, passed it, and wound up at the Veterans Administration (now the Department of Veterans Affairs), where he spent five years as a computer systems analyst.

He was later dispatched to Indiana University, where he earned a master’s degree in public administration. He joined the budget office in 1967. There he integrated more than two dozen health-related government programs in rising to deputy director.

With a daughter in college, a financially pinched Mr. O’Neill was recruited by the International Paper Company in 1977 to be vice president of strategic planning. To his amazement, he found the company had no systematic knowledge of its strengths and weaknesses; the framework Mr. O’Neill created set him on the path to become president of the company.

Probably his biggest career success was at Alcoa, which had suffered after making a series of poor acquisitions before he joined as chief executive in 1987. When he retired in 2000, the company’s revenues had nearly tripled, and its stock that year was the best performer on the New York Stock Exchange.

His tenure began with what Mr. Suskind called “management havoc” — discharging many top executives and revamping operations. At the same time, he won praise for improving worker safety and labor relations, increasing productivity and fostering an egalitarian open-door policy with his employees.

Mr. O’Neill had been friendly with President George H.W. Bush and, just after joining Alcoa, turned down an offer to become his secretary of defense. Mr. O’Neill later encouraged Mr. Bush to break his pledge not to raise taxes. When Mr. Bush did raise taxes, which proved politically damaging to him, and was rebuked by the United States Chamber of Commerce for the move, Mr. O’Neill pulled Alcoa out of the organization.

After he left George W. Bush’s cabinet, Mr. O’Neill served on many boards and returned to the Pittsburgh Regional Healthcare Initiative, a consortium of hospitals, associations and business that he had helped found in 1997.

One of the most unlikely episodes of Mr. O’Neill’s Treasury tenure was his four-nation trip to sub-Saharan Africa in the company of Bono, the lead singer of U2 and anti-poverty activist.

“I don’t have time to be a ballerina barre for a rock star,” Mr. O’Neill complained to an aide when Bono first asked for his help. “I’ll give him a half an hour.”

But he soon decided that he needed to see what programs worked if he were to support sending more money to Africa, and the pair set off, accompanied by a sizable international media contingent.

“Come on, let’s step up for a picture,” he said to Bono at one point in Ghana after they had donned Ghanaian robes and hats. “So what if we never live this down.”

Peter Keepnews contributed reporting.