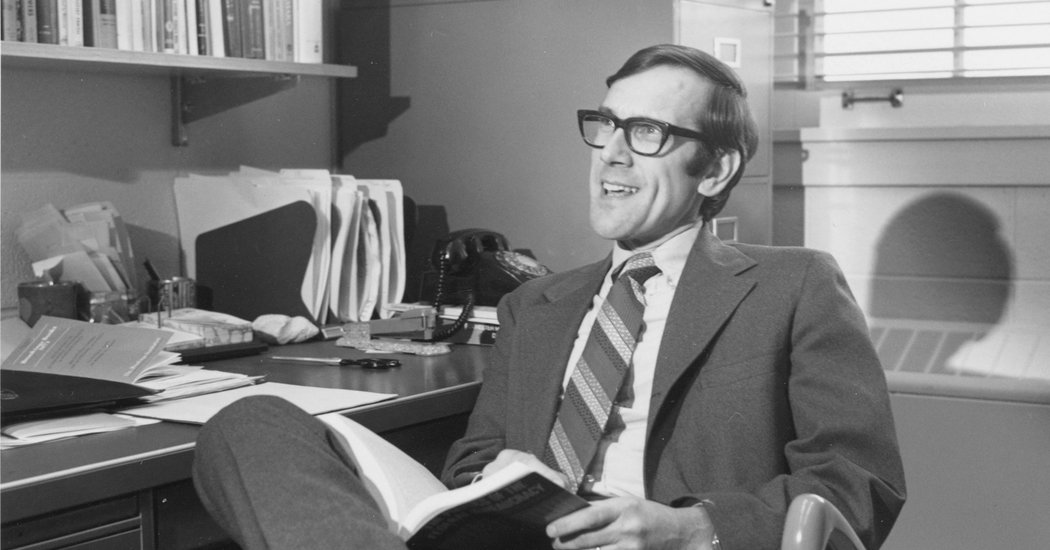

Richard F. Fenno Jr., a political scientist whose close-range research of how Congress and different elements of presidency truly work broke new fl

Richard F. Fenno Jr., a political scientist whose close-range research of how Congress and different elements of presidency truly work broke new floor in a discipline that may be preoccupied with dry coverage papers and voting information, died on April 21 at a nursing residence in Rye. N.Y. He was 93.

His son Craig stated the trigger was presumed to be the coronavirus, although his father had not been examined.

Professor Fenno, who taught on the College of Rochester in upstate New York for 46 years, wrote 19 books, most specializing in the Home or Senate. Some, together with “The Making of a Senator: Dan Quayle” (1989) and “Studying to Legislate: The Senate Training of Arlen Specter” (1991), had been about particular person members. Others handled broader topics. There was, as an illustration, “Going House: Black Representatives and Their Constituents” (2003).

“Illustration,” he wrote in that guide, “is, at backside, a house relationship, one which begins within the constituency and ends there.” And thus he visited the representatives he wrote about not simply in Washington, however of their districts.

“House, not Washington, is the place the place most Home member-constituent contact happens,” he wrote, “and the place the place judgment is finally rendered.”

In 1968, an eventful year in American history, one of those students, Robert Sachs, came to him with an idea that Professor Fenno turned into a University of Rochester institution: the so-called Washington Semester, in which a student receives credit for working in the political sphere in the nation’s capital.

“Having heard Professor Fenno speak enthusiastically about shadowing members of Congress and senators in the course of his research,” Mr. Sachs said by email, “I thought maybe I could also learn this way, and get involved in the world of politics at the same time.”

Mr. Sachs, whose subsequent career included working on Capitol Hill and in the executive branch, was the first of many to take the Washington Semester, a relatively new idea at the time. Another was Heather A. Higginbottom, who became a deputy secretary of state in President Barack Obama’s administration.

“The Washington Semester Program was brilliant in its simplicity,” she said by email. “Fenno understood that to truly understand how policy is made — the dynamics that contribute to decision making — you needed to be up close and personal. A full-time internship on Capitol Hill for an entire semester provided a front-row seat for how legislation was made, and he made sure you were appreciating the various factors at play.”

The experience, she said, stayed with her.

“That one internship nearly 30 years ago completely informed my approach to politics and policy,” she said. “It grounded me in the pragmatism of policymaking.”

Richard Francis Fenno Jr. was born on Dec. 12, 1926, in Winchester, Mass. His father was in the coal business. His mother, Mary (Tredennick) Fenno, died when he was a young child.

After serving in the Navy during World War II, Professor Fenno graduated from Amherst College in 1948. He earned a Ph.D. in political science from Harvard in 1956 with a dissertation titled “The President’s Cabinet,” which became his first book, published in 1959.

“This book is at once a first-rate story of what makes the American political system tick (making it of interest to the general reader) and a perceptive study of the cabinet in recent years,” The Boston Globe wrote in a brief review.

Professor Fenno’s later books included “Home Style: House Members in Their Districts” (1978), in which he explored the individual styles that members of Congress affected in their home districts to help secure re-election. The book discussed what has come to be called “Fenno’s paradox”: the oddity that while most people vilify Congress as a whole, they have good opinions of their own representatives.

“It is easy for each congressman to explain to his supporters why he cannot be blamed for the performance of the collectivity,” Professor Fenno wrote, because “the internal diversity and decentralization of the institution provide such a wide variety of collegial villains to flay before one’s supporters at home.”

In “Congress at the Grassroots: Representational Change in the South, 1970-1998” (2000), he examined how two men, Jack Flynt and Mac Collins, represented Georgia congressional districts in different eras. The goal, as in his other portraits, was “to see them as flesh-and-blood, multidimensional individuals and not just as part of a widely condemned category of ‘politicians.’”

Among his students was Wendy Schiller, now chairwoman of the political science department at Brown University. “Fenno created the modern study of Congress,” she said in a statement, “with his pathbreaking scholarship on House and Senate members, legislating in the halls of Congress and campaigning on the streets of their districts.”

Professor Fenno married Nancy Davidson in 1948. She and his son survive him, along with a sister, Elizabeth Blucke, and two grandchildren. His older son, Mark, died in 2017.

Professor Fenno wrote about Congress during periods of bipartisan statesmanship exemplified by leaders like Senator Howard H. Baker Jr., Republican of Tennessee, and during more rancorous recent times. Throughout, he maintained a focus on how politicians interacted with constituents and won their long-term confidence.

One of his later books, “Congressional Travels: Places, Connections, and Authenticity” (2007), came about when he was struck by the national attention and bipartisan affection accorded to a relatively anonymous House member, John Joseph Moakley, a Massachusetts Democrat who served for 28 years, when he died in 2001. Mr. Moakley’s funeral drew 900 people.

“The explanatory story I wish to tell,” Professor Fenno wrote, “begins with a reminder: that a House member’s designation, as prescribed in the U.S. Constitution, is not Congressman, it is Representative. And whereas ‘congressman’ or ‘congresswoman’ tends to call our attention to a House member’s Capitol Hill activities and to his or her relationship with colleagues, ‘representative’ points us toward a House member’s activities in his or her home district and to relationships with constituents.”

“We could know all there was to know about Moakley’s life in Washington and not explain the attendance at his funeral,” he continued. “I will argue that he was not a memorable congressman but he was a memorable representative.”