A pair of cases are currently pending before the Supreme Court that could fundamentally rewrite the rules of US elections. Both cases are redistri

A pair of cases are currently pending before the Supreme Court that could fundamentally rewrite the rules of US elections.

Both cases are redistricting cases. In Moore v. Harper, the North Carolina Supreme Court struck down gerrymandered congressional maps drawn by the state’s Republican legislature. In Toth v. Chapman, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court selected a congressional map for the state after its Republican legislature and Democratic governor deadlocked on what that map should look like.

In both cases, Republicans claim that state courts are not allowed to intervene in redistricting cases because something called the “independent state legislature doctrine” forbids them from doing so.

In the worst-case scenario for democracy, should the Court embrace this doctrine, state constitutions would cease to provide any constraint on state lawmakers who wish to skew federal elections in their party’s favor. State courts would also lose their power to strike down anti-democratic state laws. And state governors, who ordinarily have the power to veto new state election laws, would lose this veto power.

As Justice Neil Gorsuch described this approach in a 2020 concurring opinion, “the Constitution provides that state legislatures — not federal judges, not state judges, not state governors, not other state officials — bear primary responsibility for setting election rules.”

This worst-case scenario isn’t a foregone conclusion, but it’s decidedly within the realm of possibility. The Court might also implement the doctrine selectively, holding, for example, that state supreme courts typically cannot toss out gerrymandered maps, but that state governors can veto these maps.

Four members of the Court have already endorsed this doctrine, despite the fact that the Supreme Court has repeatedly rejected it over the course of more than a century. Along with Gorsuch, Justices Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito, and Brett Kavanaugh all embraced it in lawsuits seeking to alter which rules would govern the 2020 election.

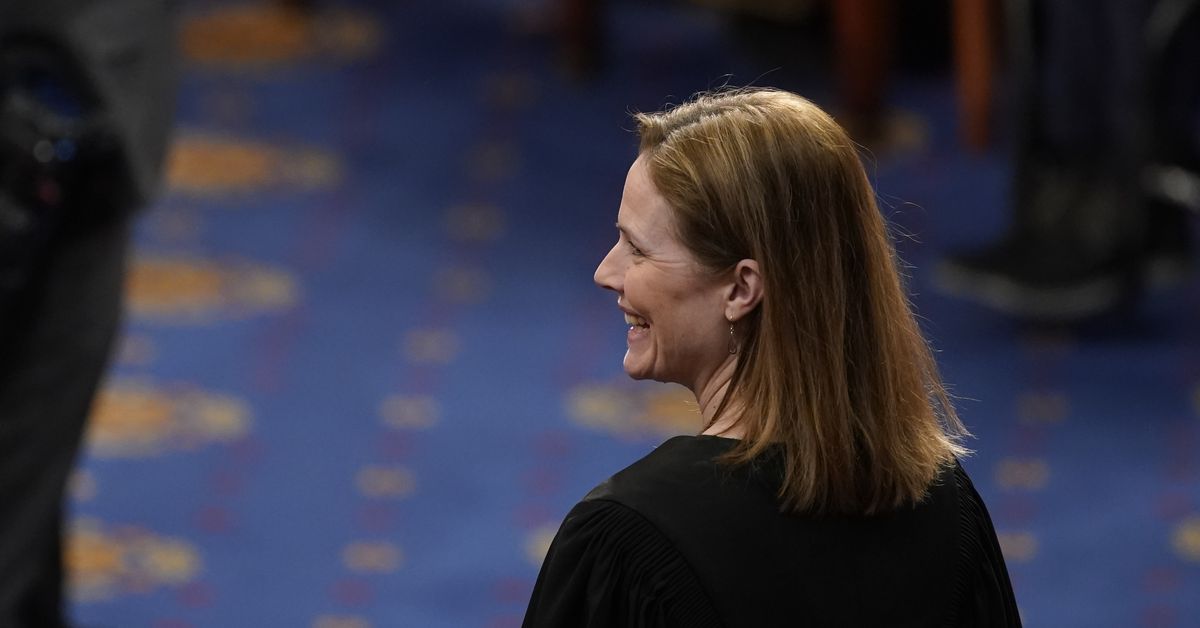

Meanwhile, the three liberal justices plus Chief Justice John Roberts have all signaled that they will not overrule the more than 100 years’ worth of Supreme Court decisions rejecting the independent state legislature doctrine. So, unless Thomas, Alito, Gorsuch, or Kavanaugh has an unexpected change of heart, the fate of American democracy is now in Justice Amy Coney Barrett’s hands.

Barrett is a conservative appointed to the Court by former President Donald Trump. But her thoughts on the independent state legislature doctrine are not yet known. Indeed, when Sen. Amy Klobuchar (D-MN) asked Barrett about Smiley v. Holm, a 1932 Supreme Court decision rejecting the doctrine, during Barrett’s confirmation hearing, the future justice said that she wasn’t even aware of this case.

It also is possible that the Supreme Court will defer its decision on whether to implement this doctrine until a future case. As the parties defending the North Carolina Supreme Court’s decision in Moore explain in their briefs to the Supreme Court, a state law — one enacted by the state legislature — explicitly authorizes state courts to hear redistricting cases. So Moore is an especially poor vehicle for the Court to apply the independent state legislature doctrine.

Just last month in Merrill v. Milligan, Justice Brett Kavanaugh wrote an opinion suggesting that federal courts should not interfere with state election laws during an election year — 2022 is an election year and the Supreme Court is a federal court. So, in the event that Kavanaugh wants to act consistently with his opinion in Merrill, he should not touch North Carolina’s or Pennsylvania’s congressional maps until after the midterm elections have passed.

But even if Kavanaugh does come down with a bout of consistency in the Moore and Toth cases, the broader fight over the independent state legislature doctrine is not going away. Ultimately the Court — and Barrett in particular — will need to decide whether to toss out more than a century of settled law, and whether to make the United States a fundamentally less democratic nation in the process.

What is the independent state legislature doctrine?

The independent state legislature doctrine derives from a deceptively simple reading of the Constitution, which provides that “the times, places and manner of holding elections for Senators and Representatives, shall be prescribed in each state by the legislature thereof.” A separate provision says that presidential elections shall also be conducted in a manner determined by the state “Legislature.”

Both clauses refer to state legislatures, not state courts or state governors, so the idea behind the independent state legislature doctrine is that the legislative branch of each state gets to decide how federal elections are conducted without any input whatsoever from the other branches.

But there are three very good reasons to reject this reading of the Constitution.

1. The Supreme Court has repeatedly rejected the independent state legislature doctrine

The first reason to reject the most conservative justices’ reading of the Constitution is that the Supreme Court has considered it several times over the course of more than 100 years. And it has rejected it every single time.

This issue first arose in Davis v. Hildebrant (1916), which asked whether state election laws can be altered by a popular referendum. In Davis, the Ohio legislature drew congressional maps, but those maps were later rejected under a provision of the state constitution that allows the people of Ohio to veto state laws via a referendum. The Court determined that Ohio’s referendum was valid in a unanimous opinion.

Davis established that the word “legislature,” as it is used by the relevant provisions of the federal Constitution, does not refer only to the body of elected representatives who form a state’s legislative branch. Instead, it refers to any individual or group of individuals who possess the power to make laws within a state — what the Court referred to as the “legislative power.”

Under the Ohio constitution, Davis explained, “the referendum was treated as part of the legislative power,” and thus “should be held and treated to be the state legislative power for the purpose of creating congressional districts by law.” That is, because the Ohio constitution gave the people of the state the power to veto laws by referendum, this power was part of the legislative power in that state. And so the voters who cast ballots in a referendum are part of the state “legislature” for purposes of the federal Constitution.

The Court reached a similar conclusion in Smiley v. Holm (1932), which asked whether a state governor is permitted to veto a bill impacting federal elections. Under the independent state legislature doctrine, the answer to this question is “no,” because the governor is not part of a state’s legislative branch. But Smiley rejected that reading of the Constitution, finding that state election laws should be enacted in exactly the same way that any other state law is enacted.

The Court’s most recent case rejecting the independent state legislature doctrine is Arizona State Legislature v. Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission (2015), which asked whether a state could use a bipartisan commission to draw congressional maps. Once again, the plaintiffs claimed that such a thing is not allowed — because a commission is not the state “legislature” — and once again, the Supreme Court rejected this argument.

Summarizing its past decisions, the Court explained that “our precedent teaches that redistricting is a legislative function, to be performed in accordance with the State’s prescriptions for lawmaking, which may include the referendum and the Governor’s veto.” Arizona State Legislature held that the voters of a state could also enact, via a ballot initiative, a state law transferring the power to draw legislative maps to a commission.

As recently as 2019, all four of the current justices who later endorsed the independent state legislature doctrine (once that doctrine seemed likely to bolster Trump’s chances of winning the 2020 election) also appeared to reject it.

In Rucho v. Common Cause (2019), the Supreme Court held that federal courts may not hear lawsuits challenging partisan gerrymanders. But Rucho also said that states may place constraints on a state legislature’s power to draw congressional maps — that “provisions in state statutes and state constitutions can provide standards and guidance for state courts to apply” in partisan gerrymandering cases. Rucho seemed to endorse “constitutional amendments creating multimember commissions that will be responsible in whole or in part for creating and approving district maps for congressional and state legislative districts.”

Thomas, Alito, Gorsuch, and Kavanaugh all joined the Court’s opinion in Rucho.

2. During America’s founding, people rejected the independent state legislature doctrine

There is also powerful evidence that the people who wrote our Constitution and their contemporaries rejected the idea that state legislatures have an unchecked power to write laws governing federal elections.

As legal scholars (and brothers) Vikram and Akhil Amar explain in a forthcoming paper, four states adopted state constitutional provisions during President George Washington’s first term that restricted the power of state legislatures to set the rules governing federal elections. Those states’ constitutional provisions, enacted in the very first days of the republic, wouldn’t have been allowed if the independent state legislature doctrine is actually mandated by the Constitution.

Similarly, the Amars write, “at least two early states that provided for vetoes for general legislative action employed such vetoes in the process by which federal election rules were made.” In Massachusetts, “bills regulating federal elections were not considered by the legislative houses alone but were presented to — and subject to disapproval by — the governor.” And in New York, “such bills were subjected to a council of review that included not only the governor, but also members of the state judiciary.”

So, as the Constitution was understood by early Americans, state legislatures did not have free rein over how federal elections would be conducted in their state. Rather, the state legislature’s power could be checked by the state constitution, the state governor’s veto, and the state judiciary.

3. The independent state legislature doctrine is unworkable

If the independent state legislature doctrine is correct, then the state judiciary is cut out of the process of determining how a state runs federal elections. But such a framework is unworkable because, after the state legislature passes a law, someone has to determine how to apply it to individual elections.

Imagine that North Carolina’s next US senatorial election is extremely close — say that initial counts show the Democratic candidate up by only 100 votes. Imagine, as well, that the Republican candidate identifies 500 ballots that arguably were cast in violation of state law. The outcome turns on whether these ballots were lawfully cast. If they are counted, the Democrat wins; if they are not counted, the Republican wins.

Someone has to decide whether to count these ballots, and in the American system of government, the institution that makes this decision is the state judiciary. Yes, the state legislature writes the statute governing which ballots are counted, but state courts have to determine how that statute applies to a particular case. As the Supreme Court held in Marbury v. Madison (1803), “it is emphatically the duty of the Judicial Department to say what the law is.”

Now consider the facts of the Moore case, the North Carolina redistricting case that is currently pending before the US Supreme Court.

In that case, a provision of the state constitution arguably forbade the maps drawn by state lawmakers. Moreover, as law professor and election law expert Rick Hasen points out, the state legislature itself proposed the provision of the state constitution that the state supreme court relied on to strike down North Carolina’s gerrymandered maps. So this isn’t even a case where the judiciary is overruling the state legislature. It’s a case where the courts must decide whether a congressional map enacted by the legislature conflicts with a state constitutional provision that was also endorsed by the legislature.

The Moore case, in other words, is similar to the hypothetical I raised involving a close election with contested ballots. In both cases, a valid law is already on the books governing how North Carolina should conduct elections. And, in both cases, it is the job of the judiciary to decide how that law applies to an individual case.

If the state judiciary does not have this power, then state election laws become meaningless. There will inevitably be disagreements over what the law means. And the only way to resolve those disagreements is for an adjudicative body to issue binding decisions announcing what the law actually says.

The independent state legislature doctrine is an attack on democracy

If the Court embraces this doctrine in the Moore and Toth cases, the immediate result is likely to be two significant victories for Republicans in redistricting cases. But the broader implications of such a decision would be much larger.

For one thing, it could mean that governors would lose their power to veto laws governing federal elections, including congressional redistricting bills. States like Wisconsin and Michigan, with Republican legislatures and Democratic governors, would almost certainly respond with a wave of unvetoable laws making it harder for Democrats to win elections.

And recall that the independent state legislature doctrine purportedly applies with equal force to congressional and presidential elections. So state lawmakers could potentially enact unvetoable laws giving an advantage to their party’s presidential candidate. They could close precincts in heavily Democratic cities, forcing many Democrats to wait hours to cast a ballot while rural and suburban Republicans breeze through their lines. They could even enact a Georgia-style law permitting the Republican Party to seize control of election administration in major cities.

Again, the idea behind the independent state legislature doctrine, at least in its strongest form, is that state constitutions may not constrain a state legislature’s power to write laws governing federal elections. A governor cannot veto these laws, and a state supreme court cannot strike them down. It’s not even clear if state supreme courts would be allowed to interpret those laws in ways that the US Supreme Court’s Republican majority disapproves of.

That’s not a recipe for free and fair elections.