A bipartisan group of senators hoped to translate a gun control framework into actual legislation by Friday. But once again, they’ve run into some

A bipartisan group of senators hoped to translate a gun control framework into actual legislation by Friday. But once again, they’ve run into some roadblocks.

While Republicans and Democrats were able to reach an agreement on a framework that includes incentivizing states to pass red flag laws and enhancing background checks for people 21 and under, conflicts have emerged on exactly how far some of these provisions should go.

Republican negotiators believe Democrats are being too expansive in their proposals and would like to ensure they don’t act too aggressively in curbing access to firearms. In particular, there’s a split over closing what’s known as the “boyfriend loophole,” and figuring out how grant money dedicated to strengthening “red flag” laws can be used.

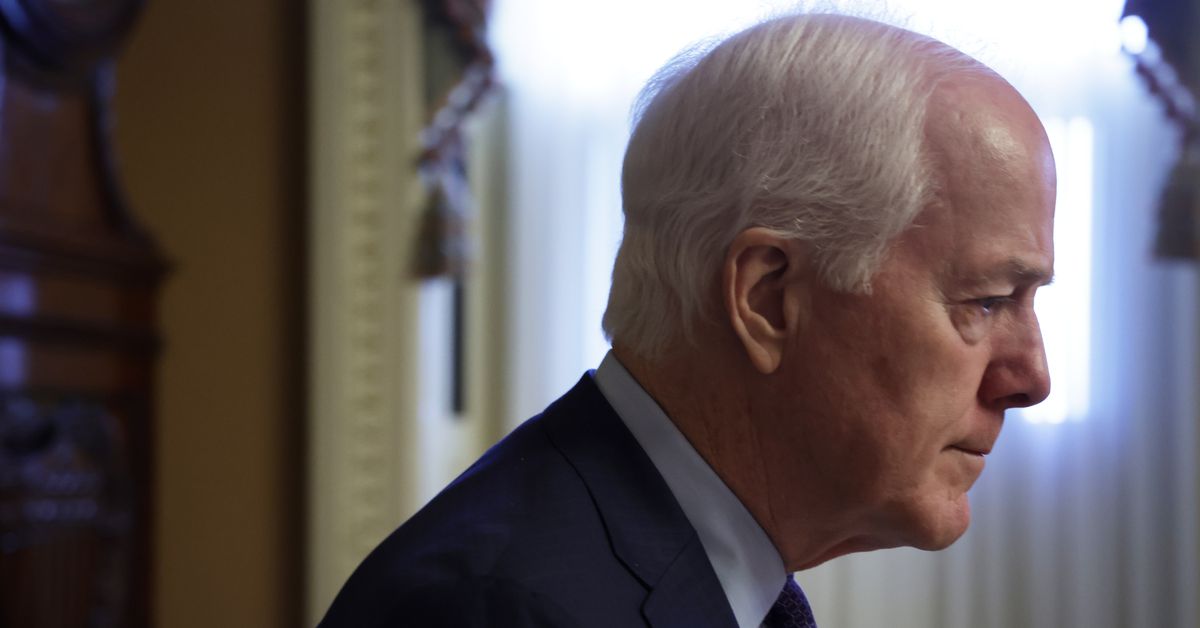

“At some point, if we can’t get to 60 [Senate votes] then we’re going to have to pare … some of it down,” Sen. John Cornyn (R-TX), the lead Republican negotiator, told reporters on Wednesday.

Lawmakers have a tight timeline; they want to pass legislation before leaving for their July 4 recess at the end of next week. The concern is, if talks drag on longer, they’ll lose momentum and fail. Sen. Chris Murphy (CT), the Democrat leading talks, was still cautiously optimistic that the team could get a bill done, though that’s likely to hinge heavily on how much progress gets made in the next few days.

“Our staff is currently drafting legislative text on … areas of agreement as we work through the final sticking points,” Murphy said in a Thursday statement. “I believe we can bring this to a vote next week.”

The two points of contention, briefly explained

There are two major areas that have emerged as sticking points: Closing the “boyfriend loophole” and specifying where grant money associated with “red flag” laws can be used.

- “Boyfriend loophole”: Currently, people who have domestic violence convictions are barred from owning a firearm, though this restriction only applies if a person has been married to, lived with, or has a child with the victim. The gap in the policy is known as the “boyfriend loophole” because it excludes people who are dating but don’t fall into the other categories.

Closing the “boyfriend loophole” has been a longstanding goal for domestic violence advocates, though Republicans have pushed back against it for years because some view it as going too far in policing gun access. Democrats, for example, have repeatedly called to tighten the loophole as part of the Violence Against Women Act only to drop this demand because it’s inclusion prevented the larger bill from passing.

Now lawmakers are trying to figure out which dating partners this restriction would apply to, with Democrats aiming to keep the category broader.

- Red flag laws: One provision of the framework would provide states with grant money to incentivize them to either pass red flag laws or implement them better.

Nineteen states and the District of Columbia already have these laws, which allow family members and law enforcement to petition a court to either confiscate or bar an individual from having firearms, if they are determined to be a threat to themselves or others.

Cornyn, however, has expressed concerns about the funding only being accessible to places that have these laws and noted that he’d like states like Texas — which do not have such policies — to be able to use them for other “crisis intervention” programs that address mental health.

Time is a major concern

One of Congress’s biggest obstacles — as it often is — is time.

Lawmakers are scheduled to leave town as soon as June 24 to go on a two-week recess for the July 4 holiday, and Democrats hope to nail down a vote before then. While the Senate could always cancel this recess, that has historically been unlikely. And if a vote on the bill slips much longer, it’s likely momentum on this issue could slow.

Republicans, meanwhile, have been divided on the bill. Cornyn, the lead negotiator for Republicans, has stressed, for example, the importance of moving quickly. But he has also fielded major pushback from conservative members of his caucus — and sought to water down key provisions. “Indecision and delay jeopardize the likelihood of a bill because you can’t write what is undecided and without a bill there is nothing to vote on,” Cornyn wrote in a tweet on Thursday.

If discussions were pushed past the recess, there’s no reason lawmakers wouldn’t be able to resume them in July. The main concern, however, has been how such talks have fallen apart or languished in the past when lawmakers didn’t act quickly to pass legislation. In 2019, for example, bipartisan talks around red flag laws picked up after two mass shootings in Dayton, Ohio, and El Paso, Texas, only to get stymied by Republicans and lose steam.